Why the World is Giving up on Democracy, the Science of Collapse, Plus History’s Lessons for Now

I’m Umair Haque, and this is The Issue: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported publication. Our job is to give you the freshest, deepest, no-holds-barred insight about the issues that matter most.

New here? Get the Issue in your inbox daily.

Quick Links and Fresh Thinking

- Here's a big reason why people may be gloomy about the economy: the cost of money (NPR)

- Good Riddance to Mitch McConnell, an Enemy of Democracy (The Nation)

- The birth of Fox News’s ‘migrant crime’ obsession (WaPo)

- French Senate votes to enshrine abortion in constitution, a world first (WaPo)

- ‘Extremist’ Trump economist plots rightwing overhaul of US treasury (The Guardian)

- Supreme Court Hands Trump a Win and Delays His Election Subversion Prosecution (Mother Jones)

- Nepo Babies Crowd the Runways (NYT)

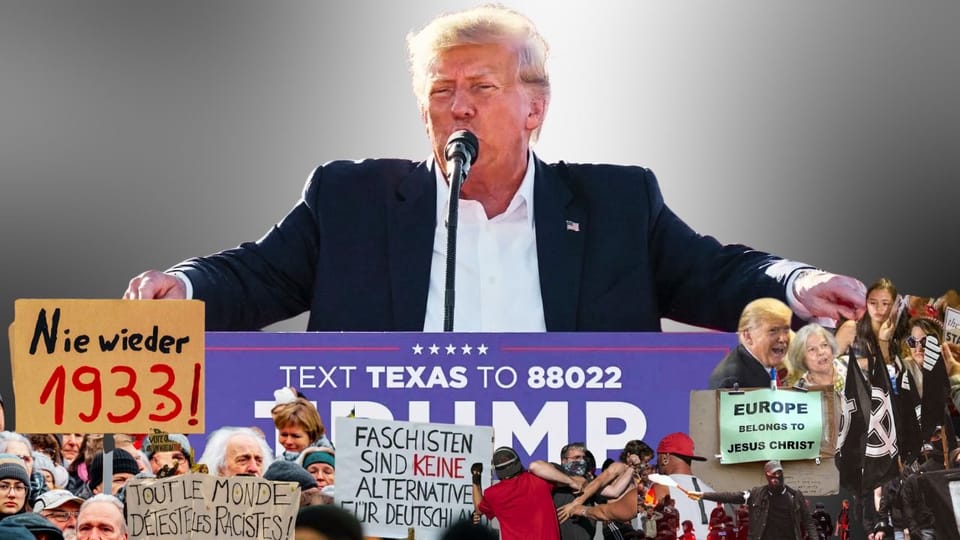

Why the World is Giving up on Democracy

How are you feeling these days? Gaza. Ukraine. Trump. Inequality. The rise and rise of lunacy, hate, conflict, spite. We live in an age where the world is going haywire. Why, though, precisely?

A new paper—and I think it’s quite an important one, for those who want to understand how everything went so wrong—sheds much-needed light on the question. It’s a meta-analysis, which looks at two competing theories of…

Two macro trends that we discuss often. One is the implosion of democracy, and the second is global economic stagnation. Let’s review them quickly.

Now: those two macro trends alone paint a grim portrait. A civilization that’s losing it’s way politically, turning away, hard and sharply, from democracy—and one that’s so unequal that the economy’s now stagnant or in fact declining for most. The big question’s been: are these trends linked?

I say the big question in a way that makes me, at least, sigh. It’s a big question in American discourse and thinking, which isn’t exactly the sharpest in the world. Looking at history, you’d conclude, yes, these trends are intimately linked—but thanks to American discourse, a competing explanation emerged.

Let me quote from the paper:

So: two competing theories. One, economics is behind the world’s authoritarian wave, and democratic implosion. Two, “culture” is the cause of it. Which one have you believed in? Which one makes more sense to you? I’ve long been on the side of the former, because, of course…let me try and explain.

When we say “culture” is behind democratic implosion, the masses’ sudden, furious turn to regress, spite, even hate and conflict and violence, what do we mean? You see, the authoritarian turn, of course, is worldwide. I mean that quite literally. It affects, by now, every corner of the globe, from the US to China to India to Russia and beyond.

So if the menacing authoritarian turn the world’s taken is just that, global, then how can “culture” be behind it? Because of course none of these places are remotely the same, or even similar, culturally. Let’s just take the example of America and Europe. What do rural Texans and those in towns in Germany or Italy have in common, culturally—all places where the hard right is ascendant? Nothing whatsoever, in fact—the cultures are, if anything, polar opposites, dramatically so. Put an Italian or a German in Texas, or vice versa, and watch culture shock ensue.

The same is true, only even more drastically, of, for example, Americans and Indians. Both nations have taken a sharp turn towards the right—Trumpism still ascendant in America, Indian democracy savaged by its fanatics. But of course America and India have little to nothing in common culturally—especially when we speak in more formal terms, like whether or not cultures are materialistic and individualistic, or not.

So to my mind, culture has been not just a weak explanation for the authoritarian meltdown the world’s seen—but an incredibly weak one. And it’s telling that it only really has a place in American discourse. When we say “culture” in American thinking and discourse, it’s all too often a polite placeholder for “race.” “Culture” has never been a formal, social scientific explanation with much teeth—what it was was popularized in pop articles and punditry. And at that level, “culture” often means “race, and so what “culture caused the democratic implosion” meant was something like: “white people don’t like democracy anymore.” But like I said: what do a Texan and an Italian really have in common “culturally,” apart from “race,” which itself is a fictional construct? Not much, if we think about it.

Instead, what’s truer in my example is that a German from a depressed region, an Italian from a post-industrial wasteland, and an American from the Rust Belt all began to experience the same dynamics. The rich went from super to ultra to mega rich, to the point that figures like an Elon Musk could now single-handedly fund what the entire developing world needs for climate finance. Meanwhile, these social groups—the working class, the lower middle class, even, in some places, the managerial, or upper middle class—saw dramatic, sharp declines in their fortunes. In every way. Their cities and towns and communities fell into disrepair, their living standards fell, and their opportunities waned. What these social groups shared, in other words, was an economic experience—one of stagnation and decline.

The (Emerging) Science of Social Collapse

Now, to settle this debate, we have scientific evidence—in the form of a meta-analysis. And what does it find? Let me quote you some key bits from the paper.

Although we found significant heterogeneity in several dimensions, all thirty-six studies report a significant association between economic insecurity and populism… Tallying the number of successful, positive significant associations across 144 causes tests conducted in the thirty-six studies, we found that the overall share of significant positive associations (successes) was 67 per cent, with each causal treatment exceeding the 50 per cent threshold."

Let me translate that, because those are the key results. All the research that we know of presents an unambiguous picture: economic insecurity drives the authoritarian surge. Not “culture”—which is precisely what we should expect, given history, and I’ll come back to that.

Get that? That’s, to my mind, a crucial few sentences. There was once something like a ladder of prosperity in societies. The working class could become middle class, and the middle class, while it had smaller chances of becoming immensely wealthy, was at least stable enough that there wasn’t a significant risk of falling backwards. But now that trend—and we could call this one another macro trend—has reversed: downward mobility is becoming the norm, while upward mobility has all but ceased, and that’s truer and truer down the generations. The modern far right stormed the globe by building coalitions amongst these “losers of globalization,” the middle class and working class, now downwardly mobile into a precarious underclass.

Vital—and insightful—stuff.

History’s Lessons for Our Troubled Future

All of this should begin to settle the “debate” around whether economics or “culture” caused the democratic implosion globally, which should never have been much of a debate at all. Before, I pointed out how “culture” is a poor independent variable—the world doesn’t have the same culture, and yet democracy’s imploded across it. But let’s think historically now.

What’s driven regress in the past? In the case of Nazi Germany, it was of course the Weimar Republic’s massive economic failures, which savaged living standards. In the case of post-Soviet Russia and it’s satellite states, it was the failure to develop economically, living standards stagnating, currencies in free fall, inflation exploding, and a decade plus of that turned people to demagogues who are still in power today. We can go all the way back to ancient Rome—Caesar was the West’s first proper populist, crossing the Rubicon, laying the foundations for democracy’s end, at a time when the average Roman was hungry merely for bread, to which Caesar of course added circuses.

History’s crystal clear on this topic. Periods of implosion and collapse are driven by failing economies. Failing economies mean something particular, too—economies can be said to be “successful,” as they are today, for example, in America, and yet fail to deliver for the average person, gains accruing to elites and power centers. From ancient times, wise ruling classes have maintained their grip on power through tactics like debt jubilees and generous redistribution of wealth—and when they’ve failed to do that, the results have been explosive, and often revolutionary. The horrors of Les Miserables and the vainglory of Marie Antoinette preceded the French Revolution, which, while it abolished the nobility, also brought terror to rule.

What we need to understand is that today, we are living through just such an implosive period. Our civilization is in bad shape. That’s not a message that’s easy to stomach. We prefer to numb ourselves with influencers or binge-watches than really think seriously about why and how we got here. Along the way, fake “debates” emerge, which can be unpicked with just a moment’s thought, like whether or not a numinous thing called “culture” is the culprit of implosion. We need to face the facts, which are by now clearer by the day.

The macro trends that I often discuss with you are linked. Economies going in the wrong direction are the handmaidens of democratic implosion. And yet all that is many ways just the beginning. Climate change will certainly make us poorer—dramatically so—as a civilization. What will that do to what’s left of democracy, now that we know insecurity breeds authoritarianism? Technology, too, impoverishes us now, versus makes us richer—financially, socially, emotionally, intellectually—what does that say for the future of society and politics? As we grapple with these uncertainties, we must understand the risks we’re taking now are existential. Once the lights go out, my friends, they don’t back on for times to come. What we destroy in rage and spite takes decades, sometimes centuries, to rebuild.

It’s OK to worry about the world. If you ask me, we should do it more. We don’t do it enough, whether because of fatigue, weariness, or just plain willful ignorance. But history is watching, and wondering: why haven’t we learned its lessons yet?

❤️ Don't forget...

📣 Share The Issue on your Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn.

💵 If you like our newsletter, drop some love in our tip jar.

📫 Forward this to a friend and tell them all all about it.

👂 Anything else? Send us feedback or say hello!

Member discussion