The TikTok Ban, 21st Century Exploitation, The Great Divergence, and How The Economy Went Wrong

I’m Umair Haque, and this is The Issue: an independent, nonpartisan, subscriber-supported publication. Our job is to give you the freshest, deepest, no-holds-barred insight about the issues that matter most.

New here? Get the Issue in your inbox daily.

Quick Links and Fresh Thinking

- On popular online platforms, predatory groups coerce children into self-harm (WaPo)

- Yes, the Internet Is Broken. But What Does a Fix Look Like? (NYT)

- My feeling about this presidential election? Nauseous optimism (Guardian)

- The Terrifying Christian Nationalist Crusade to Conquer America (The Nation)

- Why are so many young people getting cancer? (Nature)

- The Biden Administration vs. Climate Youth (Project Syndicate)

- As Matches falls, is the party over for luxury sites? (The Times)

- How Blatantly False Headlines Can Distort What We Believe In (SciAm)

- Elon Musk Killed Don Lemon’s Twitter Show After Ugly Interview (NyMag)

- Authors push back on the growing number of AI 'scam' books on Amazon (NPR)

America’s (Almost) TikTok Ban

You might’ve heard by now:

The legislation, approved 352 to 65 with 1 voting present, is a sweeping bipartisan rebuke of the popular video-sharing app — and an attempt to grapple with allegations that its China-based parent, ByteDance, presents national security risks. The House effort gained momentum last week after President Biden said he would sign the bill if Congress passed it.”

So. The House has voted to effectively ban TikTok, or at least force it to restructure. Now on to the Senate. Will TikTok be banned? Should it be? How should we think well about tricky issues like this?

The Second Great Divergence

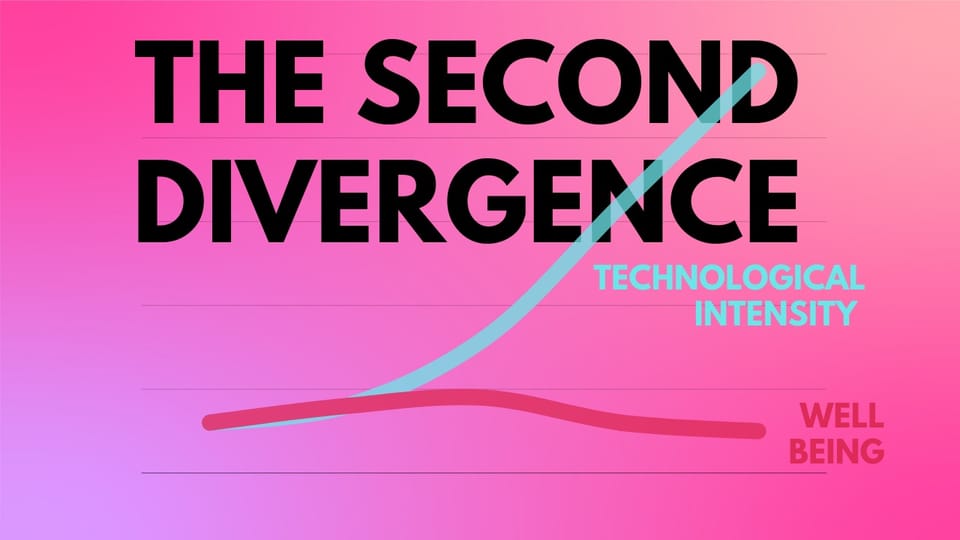

We often discuss macro trends, and I try to teach you how to think in their terms. In our age, two great macro trends are colliding, to create what I call the Second Great Divergence. Let me explain. The First Great Divergence is between GDP, or economic growth, and well-being. Economies have been nominally “growing”—but well-being hasn’t. Around the globe, living standards are flatlining or falling. The majority of people on the planet are now getting poorer. And in the largest terms, human progress itself has gone into reverse—a Great Reversal upturning a trend that held since in the Industrial Revolution.

Now let’s think about “tech,” as technology’s called today. What do you notice? Technological intensity—as might call how much people use tech, or how much time they spend with it, or how great a role it plays in their lives—has risen sharply. Ready for a telling statistic?

That’s a lot of time. Americans spend between a quarter and a third of their days with screens, or, immersed in “tech.” The number worldwide’s not too far off. Think back even just a few decades, and people didn’t spend anywhere near as much time this close to technology. So technological intensity’s skyrocketed over the last few decades, as “tech” has become part of our lives, and of course, that’s made the usual suspects of “tech companies,” Apple, Google, etcetera, not just household names, but immense fortunes.

Now put those two trends together. Living standards and well-being flatlining and or falling. But technological intensity rising. What do you see? We’re now in an age where technology isn’t raising living standards anymore.

That’s a significant rupture of a trend that held for centuries, maybe even millennia. We appear to have crossed a threshold, at last, beyond which technology no longer seems to guarantee perpetually rising living standards. And that was sort of the Big Unstated Assumption in thinking since the Industrial Revolution—technology was a magic bullet, that would eternally increase human well-being.

So: the first divergence. Economic growth isn’t resulting in greater progress or higher living standards anymore. The second one: technology isn’t, either.

The Great Reversal of Progress

You don’t have to think very hard to see just how that’s the case. And that brings us back to TikTok. Kids are glued to TikTok in a way that’s obsessive, compulsive, manic. That’s not meant to induce a moral panic—just a statement of fact. TikTok’s algorithm is designed to keep kids forever entranced, perpetually throwing new stuff at them, at seeing what sticks, every few seconds, a bizarre turbo-charged conveyor belt of “content.”

But is this good for them? We oldies have recently begun to observe the following things in young people. They don’t seem to have the same relationship to the world, anymore, that we did, and in many ways, that’s not a good thing. “Content” is disposable stuff, and yet they’re addicted to it, by design, algorithmically. But it’s not a “scene,” as this wonderful essay in the New York Times recently discussed. It promotes a sort of superficial, flimsy, skin-deep relationship with…everything…news, art, literature, music, film, relationship, history, the world.

Meanwhile, the actual world? It’s leaving young people “numb,” “paralyzed,” and “completely overwhelmed,” which are startling findings from the APA. Those are signs of trauma, and young people are traumatized precisely because they’re bearing the brunt—and facing the cataclysmic shock—of catastrophically plunging living standards. Today’s young people, from America’s Gen Z, to China’s “lying flat generation”—they’re in shock because they’re in shock. Life has gotten precarious, unstable, uncertain, and the future looks bleaker by the day.

Living standards—falling, in America’s case, for four to five generations in a row. And each of those generations has been more technologically intensive, used “tech” more, than the last, to the point that today’s young would sooner tear off their limbs than give you their smartphones. What gives here? Why isn’t “tech” raising living standards anymore?

This is, like I said, a profound reversal in deeply historic terms, and we should all be curious about it, if not troubled by it.

“Tech” and Technology

I’ve put the word “tech” quotes. Why? To make a point. Let’s think about technology. What is it? We economists define it very simply, and I think that the economics definition of it is a very clear way to think about it. Technology is stuff that saves labour. So we use the phrase “labour saving technology.”

Think back in history. The wheel: technology. It saved the labour of manpower, journeys by foot. Fast forward a few millennia, and along came the steam engine. That saved even more labour—this time, not just manpower, but horsepower. Then came the combustion engine, the motor, the stuff of the Industrial Revolution proper—and that saved staggering, immense amounts of labour, as factories were built that could churn out what were finally called “commodities” on a…well…”industrial” scale.

What happened next in this story of technology saving labor? Then came the era of appliances. Think of the 1950s and 1960s, the heyday of these new miraculous things called appliances, which suddenly transformed domestic life. The household itself became a thing devoted to recreation, not just labor—because suddenly, machines could do your dishes, laundry, cleaning, and so on.

So for millennia now, technology’s saved labor, and by doing that, it’s allowed living standards to rise. That’s not the whole story, of course—technology also enslaved, and that was another darker form of labor saving. It was used to make war, and that was aimed at conquest. But all that was counterbalanced by the better use of tech, which was innocuous labor saving, and those “savings” in labor are what allowed civilization to flourish in the positive sense. No longer having to be subsistence farmers or menial laborers, people could devote themselves to becoming scientists, writers, artists, teachers, engineers, entrepreneurs, what have you. A surplus was created—the foundation of civilization itself.

Now think about “tech.” This stuff that we click on our smartphones. What’s different about it? Think about the question of labor savings. Is it really saving any labor?

21st Century Exploitation

When I think about it, “tech” is very different from technology. Technology, like the wheel, or the engine, saves labor. But “tech” appears to create labor. That’s exploitation in a new, dystopian sense.

Let’s now go back to TikTok and Facebook and their ilk. What labor is being saved on TikTok? Facebook? It’s hard to say. Instead, new forms of labor have been created. There young people are, slaving away at this game of maximizing their followers or fake “friends,” or seeing perfect Instapeople, all of which induces envy, disappointment, jealousy on a scale that appears to be leading into an historic mental health crisis. It stresses people out and depresses them.

All of this we might call “emotional labor,” to use a favored term of the left, or “relational labor.” You don’t do this stuff because you enjoy it, that much—but because you have to, since everyone else in your class or school is busy churning out posts or “content” or maximizing friends and so on. It’s become a kind of labor that we’re doing—hence, the old term for it: “used generated content.”

This labor is making immense amounts of money for Big Tech, of course. Without people doing all this labor, for free, how much would Facebook or TikTok or Google or any of them really be worth? Only Apple, really, actually makes stuff. The rest of them just provide “platforms,” or servers, really, to be filled with stuff that “users” make, for free.

This of course has created a startlingly lopsided economy. Good luck affording a house in San Francisco—even on princely “tech” income. The entire economy’s been warped by the wierd, dystopian inequality of Gigantic Companies that basically get richer and richer from people’s free labour.

This entire economy rests squarely on the notion of labor-creating—not labor-saving—“tech,” which is how “tech” is different from genuine technology. And because it does that, of course, this is an extractive economy, which lets the bad apples rise to the top. If I’m basically creating labor for you to do, so I get rich, and all you get is poor, stressed, and depressed, and I don’t even pay you—I’m not creating much of any real value, just extracting it from you.

So why do people do it? Why do they do this unpaid labor for this weird communist-capitalist industrial complex of labor-making “tech,” in which people do the work for free, and “tech” is used to extract maximum profit from it?

There are a couple of answers to that question. Some platforms pay their users, a relatively pittance, still, but at least it’s something—like YouTube. Most, though, don’t, because they rely on basically addiction: they’re open about dopamine hits being used to create addicts, which is what “users” have become, and were maybe always going to end up as, given how contemptuous that word is of people. I used to call all that “the dopamine economy,” and I was sort of being metaphorical, in a way, but they took it literally, and designed a whole business model around it, which is sort of amazing, in a bleak kind of way.

Tech isn’t technology. It’s a thing that looks like technology. But its effects are precisely the opposite of what technology is, does, accomplishes. It’s sort of counterfeit technology. Not the wheel, really, but the Trojan horse, in a way, maybe. Instead of saving labor, it creates labor—direct labor, the world of producing “content,” the emotional labor of being stressed and depressed about it, the relational labor of being faux “social” about it, and so on. And all of that is seriously warping the economy, because now we have a class of people getting ultra rich from this extractive activity, while the modern day laborers are…us…our kids…our grandkids…young people…everyone…doing all this stuff…for free…or worse, just to get another hit of self-esteem, self-worth, a thrill of status, a rush of dopamine.

Lab rats, sadly, isn’t too far off the mark, in this case.

So should we ban TikTok? I don’t know, but at least now you have a way to think about it well.

❤️ Don't forget...

📣 Share The Issue on your Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn.

💵 If you like our newsletter, drop some love in our tip jar.

📫 Forward this to a friend and tell them all all about it.

👂 Anything else? Send us feedback or say hello!

Member discussion